From a physical perspective, in taiji (tai chi) we are fundamentally training balance, flexibility, coordination, power, efficiency of force exertion, sensitivity/reaction, agility, and confidence. This is the gong of gongfu—without which technique is empty. All of these are, of course, foundational to any martial skill.

Of course one can list differences between internal and external arts, and these differences are especially evident in the practices taught to beginners. Beginners in external arts often start with linear movement—kick hard, punch hard. Beginners in internal styles start with training the mind and efficiency of movement. Eventually, though, these paths cross—internal art practitioners develop explosive speed and power, and at higher levels external practitioners incorporate softness, relaxedness and fluidity in their movement.

Application of yin and yang theory is everywhere in the martial arts and combat sports. Wrestling, judo—grappling of any kind—all strive to use the opponent’s force against them—to be yin where they are yang, and vice versa. And nearly every martial art holds, as a basic strategy, that when attacking high the lower body is vulnerable, and that when attacking low (or with the legs), the upper body is vulnerable. Rootedness and balance is learned in all combat sports and martial arts. Once this baseline skill is learned, the game between two players is to learn to unbalance an unwilling opponent to create an opportunity, through either grappling or footwork, to make a successful attack.

Which brings us to push-hands.

Push-hands application in the external arts

Following is a transcript from a video of a MMA seminar that I found on Youtube:

“Feel it. Try to break his balance. Feel the transition—that’s the time to push him down at a minimum of your physical effort. You have to control yourself. You have to feel it. Everything should be very very easy. My task is to feel it. Generally, I can stand straight. The main thing, you should feel it. Just feel it. For example, when he’s losing balance use it (to punch/kick). It’s not complicated, but you have to feel it. But since I am breaking his torso all of the time, I can feel him thanks to this. Don’t try to break each other fully. Don’t try to apply maximum effort. Try to switch on the muscles necessary for this takedown. Nothing difficult here, just take him down. Just feel it.”

Listening to your partner’s balance and sensing where they are vulnerable to attack, and then attacking with minimal energy expenditure. This is, in a nutshell, push-hands training—learning to maintain one’s physical and mental balance while creating and/or sensing vulnerability in your partner. Once they are off-balance or vulnerable, and if you have maintained your centeredness and base of support, any attack will be successful. There is even no need to attack. The real skill is in recognizing and/or creating the opportunity, while maintaining your own centeredness. If you can do this, executing the attack is nothing. If you cannot do it, you will always be vulnerable to counter attack.

Can you guess who was teaching this seminar? It was Fedor Emelianenko, one of the greatest heavyweight MMA fighters of all time, teaching a grappling session. Every word here would belong in a book about push-hands. This is taiji push-hands 101, folks.

Here is the link for this seminar. The transcription above begins at about 1:05. There is one difference between what Fedor was teaching and push-hands. In Fedor’s seminar they were engaged in a Greco-Roman wrestling type over/under body lock and a takedown from that position generally means that both persons end up on the ground, with the successful person in a dominant position. This scores points in combat sport, but for reasons explained in a previous blog, going to the ground is not a preferred outcome in taiji martial theory.

Mr. Emelianenko does also explain the importance of sensing the opponent’s balance as opportunity to strike, which is a primary purpose of taiji push-hands training. The increasing recognition of sticking to and sensing the opponent’s intention and/or using a push to take a fighter out of their stance is an evolving practice in MMA. Here are other examples of contemporary MMA fighters, as well as a couple of the greatest boxers of all time, that employ sticking and listening as a fundamental strategy.

More examples of pushands in external arts

After Daniel Cormier recently won the MMA heavyweight title from Stipe Miocic, Dominick Cruz (the announcer, and a MMA champion himself) observed that the upper-weight MMA fighting style has now evolved into a combination of “dirty boxing” and Greco-Roman wrestling. If asked by a MMA practitioner to describe taiji application, this is exactly how I would respond—that it is like a combination of dirty boxing and Greco-Roman wrestling, specializing in issuance of short-range force with any part of the body.

Dirty boxing refers to striking from a close range, engaged position, referred to as the clinch (as directly opposed to exchanging strikes from a disengaged, mid-range position as is the preference of the Queensbury rules of boxing). Close range engagement allows one to cover or hinder the opponent’s arms and is a way to negate or defend from the often significant striking power of the larger fighters. Cormier was able to strike and knock his opponent out when contact was broken between the fighters in the grappling/clinch position. In other words, Cormier used the engaged position to defend from strikes and to sense (or control) his opponent’s movement, and once he sensed that the opponent had pulled away and was vulnerable he threw a knockout punch.

I would contend that the primary skill exhibited in this MMA fight was not in the striking; it was in the skill of defending in engagement and sensing the opportunity to strike effectively without wasting energy or placing oneself in a position vulnerable to counterattack. To listen you must not be talking—you must have a degree of relaxation and quietness to sense the opponent. This again is basic push-hands application.

Anybody could throw a successful strike at a vulnerable or undefended target. It takes skill and practice to protect oneself, to remain relaxed and maintain balance, and to learn to sense the movements, intentions, and vulnerable positions of an attacking opponent. That is exactly what is learned in push-hands. A thorough analysis of methods and purpose of push-hands is beyond the scope of this article but I would quickly note that, although efficiency of force exertion is a product of internal power, “seeing how lightly you can touch an opponent” is not the primary objective of push-hands. And pushing an opponent away without counterattack may not be desirable at all—it may simply allow the opponent repeated opportunities to throw strikes from a disengaged position. That bears repeating:

although efficiency of force exertion is a product of internal power, “seeing how lightly you can touch an opponent” is not the primary objective of push-hands. And pushing an opponent away without counterattack may not be desirable at all—it may simply allow the opponent repeated opportunities to throw strikes from a disengaged position.

I predict that understanding of the benefit of sticking and listening, and the skill levels of employment of this fundamental taiji strategy, will continue to grow in MMA competitions. Such strategy may have helped Brian Ortega, for example, in his recent title challenge with Max Holloway. Holloway proved to be too skillful with his hands and footwork at a disengaged, mid-range distance; engaging at close range may therefore have been quite helpful to Ortega. In addition to defending strikes, sticking and listening at close range can also negate a speed advantage as well as offer a tactic for take-down offense or defense.

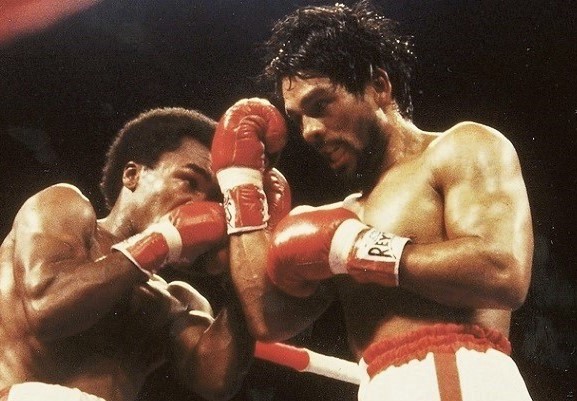

To end these observations of push-hands applications in external arts, here are a couple of additional examples from boxing. The great boxer Roberto Duran was famous for in-fighting—for staying engaged at close range to both hinder and monitor his opponent, and striking when he sensed an opening or break from the engagement. Here is an excerpt of the transcript from a youtube video on the in-fighting techniques of Roberto Duran:

“Duran was a technical master at close range fighting, with many of his hardest punches in any given match travelling only inches to his target . . . He was essentially combining grappling and striking into one movement . . . Once he had control of the arm, he had control of the fight, consistently disturbing his opponent’s balance . . . taking away their base of support and limiting their power . . . Duran was able to use the feel of his opponent’s arms against his own to interpret their intent, and defend against their movements almost simultaneously.”

Again, taiji 101—textbook instruction of the martial application of taiji push-hands emphasizing two pillars of taiji strategy; short range striking and “listening” in engagement.

From another video analysis of Roberto Duran’s style:

“His mastery of the inside was exceptional. His ability to maneuver the opponent into a position of disadvantage was uncanny . . . Even in the twilight of his career, Duran’s mastery of the inside was too much for naturally bigger and stronger opponents”

Floyd Mayweather is also famous for his close range boxing techniques—pushing or pulling the opponent into vulnerable positions for striking, and for using the elbow/forearm to block at close range. To quote the popular fight analyst Jack Slack:

“Wrestling within boxing has always been an under-appreciated facet of the game but you only need to watch Floyd Mayweather’s bouts to realize that grabbing a hold of the opponent or leaning on them can hinder a fighter’s offense far more easily than attempting to block or slip each shot.”

“Wrestling within boxing,” and visa versa, is what taiji martial strategy is all about. As Mr. Slack notes, it is much easier to neutralize/defend strikes from a close-range, engaged, position. I would further add that a close-range, engaged position may be the only hope for a smaller, weaker opponent—if a larger stronger opponent is allowed distance and therefore room to generate power, they will almost always quickly overpower the smaller opponent. Similarly, a close range, engaged position is the most efficient way to overcome difference in quickness—if you can “stick” to an opponent then your movement automatically becomes as quick as theirs. Learning to engage, defend, and “listen” at close range while maintaining balance (mental and physical) is the purpose of push-hands training.

Taiji kicks in MMA

Another way MMA has evolved is in recognizing the usefulness of low kicks. The roundhouse leg kick has been very common in MMA for a long time, but perhaps more than any single fighter Jon Jones has recently demonstrated the effectiveness of the low side kick and teep, or front/push kick. The low kicks allow the kicker to control the distance of the fight and prevent a mid-range striker from entering their effective range—something Jones demonstrated masterfully in his recent title fight with Alexander Gustafsson. All of these kicks are basic to Chen taiji forms. Low kicks (and foot sweeps), especially, are fundamental to taiji martial strategy because maintaining balance is prized above all, and the low kicks can be executed quickly with less chance for loss of balance or counter attack.

The tornado kick, back kick, and jumping front kick (which could also be a jumping knee or double knee, depending on range), all common in MMA, are also movements of the traditional Chen style taiji forms.

Distance and angles

Most styles of combat emphasize understanding of distance and angles. Indeed, controlling the distance game and dictating where the fight happens is often a significant factor in determining the victor, and for this reason many experts maintain that wrestling is the most important component of a MMA fighter’s arsenal: those with the greater wrestling skill are usually able to dictate distance.

The combined footwork/agility, kicks, and push-hands training of taiji are intended precisely to allow a skilled practitioner to dictate distance. The best strikers also all understand the importance of achieving advantageous angles for attack. Vasyl Lomachenko, considered by many to be the best pound for pound boxer today, is an expert at creating angles of attack. Here is a short gif illustrating his mastery of angles. Dominick Cruz, T.J. Dillashaw, Max Holloway and Conor McGregor are examples of champion MMA fighters who expertly utilize footwork and angles. Obtaining advantageous angles, through both push-hands (engaged grappling/neutralizing skills) and agile footwork, is also a fundamental strategy/application of taiji. Grandmaster Feng Zhiqiang’s 24 pao cui form, especially, includes a great deal of footwork in changing angles of attack, and the movement of Lomachenko above is in Grandmaster Feng’s 48 form. [Homework for 48 practitioners: where is it? Hint for students of Dr. Yang—it is one of the refined movements and is not included in the essential form.]

Stronger beating the weaker

To be sure, there are martial practitioners that rely on brute force—the stand and bang mentality. But overpowering an opponent is also a possible, and sometimes quite effective, strategy in taiji too. Achieving internal power gives one a weapon that an opponent does not have, and using that weapon unapologetically may be the most efficient path to self defense. As I quoted Grandmaster Feng Zhiqiang in a previous post, “if you have the power, everything works.” Taiji practice is about nurturing oneself and building gong—saving money in the bank and collecting interest. Martial application is very different. It is about using gong—spending the money in an emergency. Still more preferable, if at all possible you can keep your savings and make good use of the taxes you have paid by calling the police.

Conversely, taiji does certainly emphasize and prize efficiency of force exertion—but so too do many external arts. The very best fighters of any style of martial art do not expend their energy quickly and do remain relaxed and efficient in their force exertion and targeting accuracy.

Conclusion

Again, I recognize that there are many differences in training philosophies, both between and within the internal and external arts. How much sparring is necessary and at what frequency/intensity, and whether weight-lifting is important for strength or does the added bulk decrease agility and endurance, are common debates across the martial spectrum. Remember that the originators of the Chen style taiji were farmers; not ride-in-air-conditioned John Deere tractor farmers but plow-behind-oxen farmers. I would imagine that they were physically strong and tough individuals to begin with, and that nurturing themselves was an important element to balance their physical and mental well-being. I don’t know, but perhaps this was forgotten within the taiji community as taiji became more popular and some of the more famous teachers obtained relatively more comfortable jobs instructing. Though moderate aerobic activity is part of taiji (weapons training, or the jumping movements of the form, for example) and we do include aerobic agility drills as a routine part of our curriculum, I do highly recommend some cross training to students with more sedentary jobs—those of us keyboard warriors that sit at a computer far too much, for example.

It is differences in training philosophy that people are usually referring to when comparing arts. But this two-part article was specifically about understanding the commonalities of martial application. Taiji movement is taiji movement, internal power is internal power, and in application there is nothing new under the sun—effective martial strategy has been refined through trial and error by many traditions, and is demonstrated (or rediscovered) by the continuing evolution of contemporary mixed martial arts today.

There is of course a unique aspect of internal power which differentiates it from external strength, and I have detailed what I believe are the physical mechanisms of that in previous blog posts. And there are certainly differences in levels of understanding of martial strategy and application, perhaps especially with the internal arts that do not emphasize martial application in beginning practices. Internal arts practitioners, I believe, must reach the level of understanding energy (internal power) before taiji application can be truly understood. But once the level of understanding energy is achieved, and once the “eight forces and five cardinal directions” of taiji are understood to be motor programs which include, in combination, every possible direction and length (distance) of balanced force exertion, the myriad potential martial applications become quite obvious, and the differences between the internal arts, and martial strategies of any style, begin to melt away. Are not “internal” and “external” just two manifestations of yin/yang, anyway?

[WPSM_COLORBOX id=890]

Great article Scott!! I ended up starting Aikido as there was no one around to do push hands with. Same principles of sticking and listening and fascinating insights into nage uke relationships and personalities.

Thank you. Sticking and listening, though a prominent feature of taiji strategy and emphasized in push-hands, is certainly found across the martial spectrum.