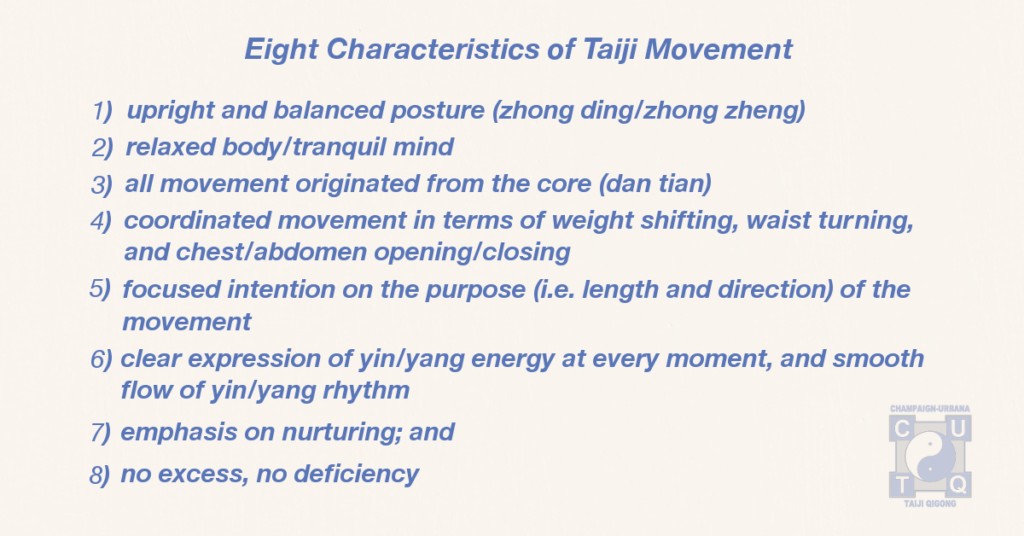

In Part I of our article “What’s the Difference?” I listed seven characteristics of taiji (tai chi) movement. Based on questions/comments received, I thought it worthwhile to expound a bit on each of these. The goal here was to make the list as succinct as possible, without omitting a key characteristic. Here again is each characteristic, with a bit of explanation following the list. After pondering, I have added one additional characteristic.

Seven Eight characteristics of taiji movement explained

1) Upright and balanced posture (zhong ding/zhong zheng). Zhong ding is often translated as central equilibrium. Importantly, this includes both physical and mental components. To quote “Taijiquan, The Art of Nurturing, The Science of Power: “The physical manifestation of zhong ding is a perfectly balanced body. A perfectly balanced body, with qi sunk to the dantian (i.e. relaxed), is achieved only by a calm and peaceful mind.” And also, “All of the martial applications of the art rely upon and seek to defend physical and mental equilibrium.” We’ll explain this further in articles about push-hands, but just say here that movements that intentionally sacrifice balance are generally not a part of taiji self-defense strategy.

Zhong zheng is translated as “straight and centered.” When the body is zhong zheng circulation is improved and the “five bows” of the arms, spine, and legs are linked as one unit. This posture is essential to generate and employ internal power. A major key here is the position of the hips/lower spine, as was addressed in the discussion of posture in the first of our articles on the mechanisms of internal power. The opposite of zhong zheng is pian—where the body is leaning or bent or “broken” at the waist. If the upper/lower body is not connected as one unit it is not possible to generate internal power.

This characteristic was meant to succinctly summarize taiji posture. To be sure, a motivated author could generate a protracted list of postural principles from a review of the literature. I have even seen expositions on how the rib cage should be positioned (silly, since it is of course attached to the spine), and fielded questions from serious taiji classic readers on “how do the toes grasp the ground?” 🙂 It is this author’s opinion that much of this is noise that obfuscates learning. “The art of knowing is knowing what to ignore,” as Rumi said. Some of these complex postural principles may be accurate, to varying degrees and with relative importance, but they are post-factum—they are the product of correct practice, not the path to realizing internal power. Indeed, the mind should be tranquil in taiji movement, and trying to think about 20 different postural principles when practicing form will hinder learning.

Zhong ding/zhong zheng is most efficiently learned in standing pole (standing meditation) practice. Taiji is moving standing pole. To quote a famous saying from the oral tradition of the internal arts in China, “1000 movements are not as good as one standing pole,” in terms of internalizing correct posture. The intellect is not needed for the mind and body to connect. Indeed, I would argue the opposite—better to get the intellect/ego out of the way and to feel the movement. The human body is far too complex to dictate positioning of every possible component. In terms of self-defense, if you are thinking about anything you are going to be too slow.

2) Relaxed body/tranquil mind. The body must be relaxed to generate internal power from the core and to express that power with the extremities. Think of a whip. If a part of the whip were replaced with a rigid material, the energy of the whip would stop there.

And, as I have included in several blog entries, the first of grandmaster Feng Zhiqiang’s 12 Principles of Practice is “Heart and spirit empty and tranquil from beginning to end.” These two are interdependent. It is not possible to have a tense mind and a relaxed body.

Taiji is one kind of qigong. A very famous saying in the oral tradition of China is “Relaxation and tranquility are the reasons why qigong can heal you.” (Note that this saying does not say that qigong can cure every acute or chronic illness. It explains why qigong can heal the physical and mental conditions that it does. If you have followed my writing, you know that I am a believer in the universality of wisdom. That tranquility can heal is is not an esoteric oriental thought. A western saying that I posted on our Facebook page conveys the same idea: “Health does not always come from medicine. Most of the time it comes from comes from peace of the mind, peace in the heart, peace of the soul. It comes from laugher and love.”)

3) All movement originated in the core (dantian). I have written in detail about the physical mechanics of internal power and refer you to these articles to understand why this is included in our short list of defining characteristics of taiji:

1. Physical mechanisms Part I

2. Physical mechanisms Part II

3. More on physical mechanisms: understanding the elastic force

These articles are the first that we are aware of to explain physical mechanisms of the power common to all internal martial arts.

Any movement with internal power, which means every movement of every taiji form, from raise hands to the finishing form, originates in the core. Indeed, this is one good way to practice to learn and increase internal power—think only (meditate) that the movement you are about to do originates in the dantian. “Grasp and hold dantian to train internal gongfu,” as Grandmaster Hu Yaozhen famously said. Relax, stay balanced and centered, forget the intellect/ego, and your body will listen to your mind and your movement will be increasingly powerful, coordinated, and efficient. Always use intention and not physical force. Because of the power of the core musculature, if you try to “muscle” this and “make the wheat grow faster by pulling the sprouts up,” you may well injure your lower back and/or hips/waist.

4) Coordinated movement in terms of waist turning, weight shifting, and chest/abdomen opening/closing. Chen Xin wrote that “taiji is the art of silk reeling,” and one of Grandmaster Feng Zhiqiang’s twelve principles was “silk reeling must be present from beginning to end.” Silk reeling is the kinetic chain that is the end product of 1) a relaxed and upright body, 2) the coordination of waist turning, weight shifting, and chest/abdomen opening/closing, and 3) movement initiated from the core. This is the trinity of physical taiji movement and what differentiates taiji movement from (mechanistically) simpler dynamic stretching movements (e.g. the classic muscle-tendon changing qigong exercises).

Silk reeling is the kinetic chain that is the end product of 1) a relaxed and upright body, 2) the coordination of waist turning, weight shifting, and chest/abdomen opening/closing, and 3) movement initiated from the core.

5) Focused intention on the purpose (i.e. length and direction) of the movement. This is the application of any taiji form—movement, and therefore the expression of force, in a specific direction and over a specific distance (short, medium, or long range). The combined direction and length of force exertion is the meaning of the eight forces of taiji: peng/lu/ji/an/cai/lie/jou/kao. We have written at length on this before; here I will only comment that the translation of peng/lu/ji/an as “wardoff/rollback/press/push” has, I believe, been the reason for considerable misunderstanding of this fundamental concept of taiji martial application.

The translation of peng/lu/ji/an as “wardoff/rollback/press/push” has, I believe, been the reason for considerable misunderstanding of this fundamental concept of taiji martial application.

Under the laws of Newtonian mechanics, every force is characterized as either a push or pull, and force is simply defined as the product of mass x acceleration. There is no other physical force. The variables of any force are magnitude, direction, and duration. Peng/lu/ji/an/cai/lie/jou/kao simply describe every possible combination of direction and duration of force expression. Taiji movement teaches one how to generate and express force in every possible direction, and over long, medium, and short ranges. What is translated as “press” (ji) is simply a push (or strike, as all strikes are an example of rapid elastic/collision force) in a forward direction. What is translated as “push” (an) is actually and quite simply a downward force.

The intensity of aerobic exercise is measured by heart rate increase. The intensity of taiji/qigong is, however, a function of the depth/degree of mind/body integration—something that is very hard to measure, and quite difficult to explain in words—it must be experienced to be known. Note importantly that this does not mean using mental force. The mind is not tense but relaxed and focused. Certain standing meditation exercises are an efficient bridge in experiencing mind/body/spirit integration when moving from meditation (wuji) to movement (taiji). It is very hard indeed to keep a high level of intensity through one entire form, and I believe impossible to do it with rote repeated form iterations.

6) Clear expression of yin/yang energy in every moment, and smooth flow of yin/yang rhythm. Taiji means balance and flow of yin/yang, so this idea has to be on the short list of characteristics. I have been told that a frequent suggestion of Grandmaster Feng to many of his closest students was to “make the yin and yang energy more clear.”

The result of clear differentiation of yin and yang is circular, flowing movement and the cyclic storing and (gentle) releasing of energy that is the rhythm of taiji movement.

7) Emphasis on nurturing. In all that we do, we are nurturing ourselves and our brothers and sisters. With correct attitude and understanding of practice, we always feel relaxed, tranquil and vitalized after practice.

Form practice does, eventually, feel very powerful. But to nurture ourselves we should always remain tranquil and practice with moderation and not overdo anything. The more internal power developed, the less you should, or even can, do form in order to avoid overuse injury. You do have to practice fajin (explosive release of energy) in order to learn it, but again this must be practiced with moderation and in a gentle and controlled manner—to attempt to shake your body as violently as you can is an inefficient path and will quite likely result in injury. (And never, ever, shake your head if/when you do release stored energy). Even in push-hands, when we begin to practice martial application and use the internal power developed in meditation, qigong, and form practice, we are always nurturing ourselves and our partners, and we should always feel revitalized after practice.

To practice with fear or brutality in the heart and the thought of defeating or harming others ultimately results only in harm, physically and mentally, to the practitioner. It is ironic that those that practice martial arts brutally are actually engaging routinely in the opposite of self-defense—they are, inevitably, harming themselves. (Most professional fighters or those involved in combat sports will tell you that injuries sustained in practice/sparring are much greater than those occurring in actual competition. How many people come to taiji because of serious injury in previous martial or other overly-intense physical exercise? ) To live healthier, stronger, wiser, and happier into old age is the purpose, and the reason why taiji first became popular in China.

8) No excess, no deficiency. This was not in the original list, but after pondering I think it an important descriptor of taiji movement. Taiji strives for perfect efficiency of movement—not a single movement that is not needed, and not a single essential movement omitted. This is the reason why you follow the teacher at his or her speed. If you are moving at the same pace and find yourself behind, you are adding unnecessary movement. If you find yourself ahead, you are omitting essential movement. Of course no two bodies are the same, and to look exactly like someone else is not the goal of form practice; it is a beginning exercise to start to understand. “From similar in appearance to similar in spirit,” as the famous saying relates.

. . . to look exactly like someone else is not the goal of form practice; it is a beginning exercise to start to understand.

Push-hands is also direct practice of no excess, no deficiency. A goal of push-hands is to neutralize just enough, without wasting energy or movement. I have yet to meet a student that does not need to learn this principle through practice. Efficiency of movement is the path to defending/attacking as fast as possible, and the essence of the “inch force” of the internal arts.

I would contend that any movement done in accordance with these eight principles is taiji movement. Other characteristics used to describe taiji movement (e.g. fluidity, power, coordination, agility) are a product of these principles. The reason taiji is practiced with slow movement is because that is the only way these characteristics can be learned and internalized—it would be impossible to start with fast movement and truly incorporate theses principles. Taiji movement and power is not natural ability. It must be learned.

The reason taiji is practiced with slow movement is because that is the only way these characteristics can be learned and internalized.

So what is your list? Have I omitted an essential characteristic of taiji movement?

[WPSM_COLORBOX id=890]